Title: Discovery of small molecules and dinucleotide analogs as STING agonist for cancer immunotherapy.

Introduction

Immune evasion via T cell exhaustion, secretion of immunosuppressive mediators and expression of proteins that modulate immune checkpoint, is a well-established hallmark for cancer (1). T cell infiltration to the tumor microenvironment has been considered to be a prerequisite for an efficient response to immunotherapeutic treatment (2,3). Hence, redirecting the immune response to the tumor microenvironment has been considered an important therapeutic route for cancer treatment (2).

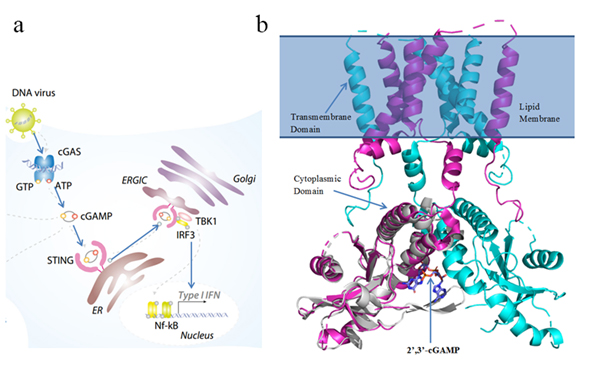

The enzyme cyclic-GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) detects cytoplasmic self DNA or tumor-derived DNA and generates the secondary messenger cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate–Adenosine Monophosphate (cGAMP) (4). cGAMP binds to the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and activates it. STING then recruits tank-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and activates interferon regulatory factor (IRF3) which triggers a cascade of downstream signaling events responsible for activation and infiltration of T cells into the tumor microenvironment and promotes antitumor responses. Hence, STING agonists with the potential to induce immune response are promising drug candidates for cancer (2,5,6).

The objective of this proposal is to determine the mechanism of STING activation by its endogenous ligand cGAMP at the molecular level and to develop novel STING agonists using state-of-the-art computer-aided drug design (CADD) techniques such as molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, classical molecular dynamics (MD) and binding energy calculation (7–9).

Aim 1: To determine the mechanism of activation of STING by the endogenous cyclic dinucleotide 2’, 3’-cGAMP.

The stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is a transmembrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Previous studies have shown how 2’, 3’-cGAMP interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of the STING dimer. However, the mechanism of how 2’, 3’-cGAMP binding leads to activation of STING and the downstream signaling events that follow is unknown. Comparative studies of the STING dimer in apo state and in the 2’, 3’-cGAMP bound state could reveal essential conformational changes and key residues involved in activation.

All-atom classical MD simulations of apo-STING and STING–cGAMP (Figure 1B) will be performed to study dynamic interactions at the binding interface and 2’, 3’-cGAMP induced conformational changes in STING. This will be followed by MM-PBSA binding free energy calculations to study binding affinities and identify residues important for binding (8). The cryo-EM structure of apo human STING (PDB 6NT5) and the cGAMP–STING complex (PDB 4KSY) will be used (10,11). Missing residues will be modeled. Simulations and binding energy calculations will be performed using GROMACS and g_mmpbsa (7,8).

Aim 2: To develop novel hydrolysis resistant nucleotidic STING agonists.

Natural cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) and derivatives have demonstrated promising antitumor activity and immunostimulating effects in vitro and in vivo. However, they are poor drug candidates due to instability and high polarity. CDNs contain phosphodiester bonds that are negatively charged and susceptible to hydrolysis by enzymes such as phosphodiesterase (2,12).

The CDN 2’, 3’-cGAMP is a heterodimer linked by one 3’-5’-phosphodiester and one 2’-5’-phosphodiester and is the most potent STING agonist in humans (Figure 1C), with a dissociation constant of 4.59 nM (13). Starting from cGAMP, hydrolysis-resistant analogs will be designed to mimic key interactions with STING by substituting linker moieties for phosphodiester bonds (Figure 1D). Molecular docking will evaluate binding interactions; binding affinities will be iteratively assessed using all-atom MD simulations and binding energy calculations (14).

Aim 3: To discover small molecules from publicly available databases with virtual screening.

Based on Aim 1, key interactions important for STING activation will be identified. Pharmacophore models will be developed to search for small molecules that bind and activate STING. This will be followed by docking to evaluate binding affinity. Promising compounds will be studied further using classical MD simulations and free energy calculations (14). Compounds from databases such as ZINC (15) or ChEMBL (16) will be used. Hits may be tested by experimental collaborators for antitumor activity.

Significance

Immunotherapy has emerged as a remarkable pharmaceutical approach to mitigate previously untreatable tumors and metastatic cancers via immune checkpoint blockade and antitumor T cell responses. However, a drawback is non-immunogenic tumors that fail to elicit T cell responses (2). T cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment can indicate effective response to immunotherapeutic treatment (3). Hence, strategies that promote T cell infiltration may improve antitumor activity.

The cGAS–STING–IRF3 pathway is a key innate immune signaling pathway (Figure 1A) (17). Cytoplasmic DNA triggers cGAS to generate cGAMP (2’,3’-cGAMP in humans). cGAMP binds STING, inducing conformational changes that lead to activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons, promoting T cell infiltration and immune response. STING is thus a promising target for antitumor drugs and vaccine adjuvants (5,13).

While structural understanding has progressed, several aspects of STING activation remain unresolved—especially how cGAMP binding leads to activation. Multiple nucleotidic STING agonists have been developed; however, many have limited stability and susceptibility to hydrolysis (12). Developing stable nucleotide-based STING agonists remains a key challenge.

DMXAA showed anti-tumor activity in mouse models but failed clinically due to lack of activity on human STING (22). Several small molecules have been reported as STING agonists (23,24), but no non-nucleotidic STING agonists are currently in clinical trials (2).

Innovation

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) methods are powerful tools frequently used alongside experimental methods. Computational approaches can help uncover mechanisms of STING activation and aid discovery of STING agonists. With growing literature and availability of full-length cryo-EM structures of apo-STING and cGAMP–STING (human), computational study of STING presents an opportunity to develop agonists targeting the cGAS–STING–IRF3 pathway.

This project is designed to study the binding mechanism of STING and 2’,3’-cGAMP and to design hydrolysis-resistant STING agonists. Potential hits may be tested by experimental collaborators. Although computationally intensive, advances in GPU hardware and MD software make long-timescale simulation more feasible. The proposed study uses standard drug discovery methods including docking, simulation, binding energy calculations, and pharmacophore-based virtual screening.

References

1. Hanahan, D. and Weinberg, R.A. (2011). Cell, 144, 646–674.

2. Marloye, M., Lawler, S.E. and Berger, G. (2019). Future Science.

3. Gajewski, T.F., Schreiber, H. and Fu, Y.-X. (2013). Nature Immunology, 14, 1014.

4. Wu, J., et al. (2013). Science, 339, 826–830.

5. Ablasser, A. (2019). Nature, 567.

6. Barber, G.N. (2015). Nat Rev Immunol, 15, 760–770.

7. Abraham, M.J., et al. (2015). SoftwareX, 1, 19–25.

8. Kumari, R., et al. (2014). J Chem Inf Model, 54, 1951–1962.

9. Sun, H. (2008). Curr Med Chem, 15, 1018–1024.

10. Shang, G., et al. (2019). Nature, 567, 389.

11. Zhang, C., et al. (2019). Nature, 567, 394.

12. Li, L., et al. (2014). Nat Chem Biol, 10, 1043.

13. Shi, H., et al. (2015). PNAS, 112, 8947–8952.

14. Pronk, S., et al. (2013). Bioinformatics, 29, 845–854.

15. Koes, D.R. and Camacho, C.J. (2012). NAR, 40, W409–W414.

16. Gaulton, A., et al. (2011). NAR, 40, D1100–D1107.

17. Ablasser, A. and Gulen, M.F. (2016). J Mol Med, 94, 1085–1093.

18. Zhang, X., et al. (2013). Mol Cell, 51, 226–235.

19. Gao, P., et al. (2013). Cell, 153, 1094–1107.

20. Jin, L., et al. (2011). J Immunol, 187, 2595–2601.

21. Liu, P., Sharon, A. and Chu, C.K. (2008). J Fluor Chem, 129, 743–766.

22. Bibby, M., et al. (1991). Br J Cancer, 63, 57.

23. Zhong, S., et al. (2019). PLoS One, 14, e0216678.

24. Ramanjulu, J.M., et al. (2018). Nature, 564, 439.